Using theatre to express, represent, sublimate, question or shake up Martinican society: Gaël Octavia, Daniely Francisque and Fabrice Théodose have made the choice. From the great story to the most intimate, these three contemporary playwrights talk about us. For Kariculture, they tell some secrets about their creations.

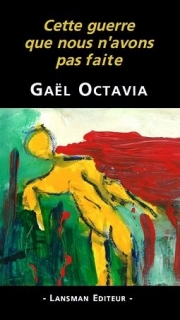

“I started to write to playwright Wadji Mouawad to tell him all that his theatre, marked by the Lebanese War, was bringing me”, says Gaël Octavia. She, a young Martinican woman, whose people had not fought in a war of decolonization, but who fantasized about it. The long letter she finally did not send became “Cette guerre que nous n’avons pas faite”.

“What I knew about her fascinated and frightened me”. Daniely Francisque had heard of Ladjablès since she was a child. She wanted the new generations, in turn, to discover this legendary Caribbean monster who reserves a fatal fate for the men she seduces. So she wrote her version of the story: “Ladjablès, femme Sauvage”.

Fabrice Théodose was the happiest of men when his daughter was born. He wanted to shout it but out of modesty, he had fun doing the opposite exercise: “Je suis en chien, man ké tchouyé kò mwen” (I’m like a dog, I’m going to kill myself). These first sentences published on his Facebook page, widely commented and liked, preceded all those that today make up “Le Monologue du Gwo Pwèl”.

From the great story to the most intimate

“Cette guerre que nous n’avons pas faite” was published in 2014, a few years after the 2009 strike and the referendum on Article 74 of the Constitution. In this work, Gaël Octavia tells the epic story of a Martinican who went to war, moving away from his alienating bourgeois comfort, to “become a man”. Between two harsh words against his mother, guilty of submission and compromise with the powerful, the Warrior explains, finally, why he never made war.

“When I read “Incendies” by Wajdi Mouawad, it echoed something very strong in me, a questioning about Martinique and independence. We haven’t fought our war of decolonization and we are perpetually fantasizing about this decolonization. Wajdi Mouawad is a dreamer who would have wanted to dream in peace but who is in the war. We are in peace and we dream of war”, she says.

He describes, in his theatre, the absurdity of this scourge: “every person who commits a violent act does so in retaliation for another violent act. Everyone is convinced that he or she is in the right. When people talk to me about solving things with violence, I want to say: wait, do you know what we’re talking about? Violence, once you start, you don’t know when it stops and what the consequences will be. Are we aware that we’re opening some kind of cage with a beast that we’re not going to control? You just have to know it. If we still decide to take the risk because it’s worth it, ok!”.

Daniely Francisque, through “Ladjablès, femme sauvage”, also questions our history and more particularly the relationships between men and women. In her play, the young Siwo, a shameless seducer, is caught at his own trap by Ladjablès, a very beautiful woman with a horse hoof instead of a foot.

“There wasn’t much documentation about her, this story has been passed down for generations through oral tradition. I found her in tales for children, in “Chronique des 7 misères” by Patrick Chamoiseau or “Esquisses martiniquaises” by Lafcadio Hearn, an Irish essayist who lived in Martinique at the end of the 19th century. It was a great Martinican lady with whom he stayed who told him the legend. This woman must have known slavery, it came from far away”, she says.

She continues: “I also found an article by André Lucrèce, sociologist: “Le corps du diable au service de la civilisation” (The devil’s body at the service of civilization). He was trying to find out where this myth came from and why this story was rooted in our imagination, why it still resonates today. He developed a reflection on the fact that the devil was the scarecrow found by religious settlers to induce in post-slavery male minds the fear of seductive women (…) I thought it was a demonized woman rather than a devil woman. She is ostracized because she’s a seductress. She does what she wants with her body, she decides, she chooses the men. She goes against the Christian education given to women”.

Even more intimate, Fabrice Théodose’s play tackles a taboo subject, the intimacy of Caribbean men’s feelings. In a long monologue, a man talks about his heartbreak, his gwo pwèl, in the hope of reconquering his beloved.

“What is amazing is the antinomy between the expression “gwo pwèl” and all the mocking side that surrounds it. When we say in French that a man has a heartbreak, we feel sorry for him. Here, we make fun of people who have a “gwo pwèl”. We’re not allowed to cry. As far as I know, this is the first time we are in the closed-door of a man who tells what he’s thinking (…) Theatre allows you to look at yourself. The person you see on stage, sé nou mèm (that’s us). My goal is to question people, society. For me the most important thing is to have feedback, discussions, to have people who ask questions”.

Writing in Martinique or with the hindsight of elsewhere

For Daniely Francisque, Martinique was the missing piece of the puzzle after a childhood in France. “Nèg pa ka mò“, her first play, was born out of a anger of a student who had not been told her story, the story of slavery. She had to go to the source, to her island of origin. Years later, she’s still there: “I’m so comfortable here, it’s a resource. Sometimes I travel, it’s very inspiring and brings me a lot of ideas, but we’re lucky to be here. There are so many stories to tell, no one will do it better than us”, she says.

And she continues her long reflection: “I think that the audience of “Ladjablès” liked the question of the collective imagination revisited. It’s important, it echoes the stories of uprooted statues. We need to see our bodies, we need representations. That’s why I do theatre, this theatre that looks like us. We are in deficit of our stories, of our bodies, of our imaginations. It’s fundamental to put that on a stage, in stories, to fix it somewhere. Can we see each other on television? Do we see each other in fictions? And how do we see each other? How are we represented? In a rewarding way? Are we proud of it? Does it inspire us? (…) The further I go, the more I realize why I do theatre, why I have this need to create. I believe that one of the pillars of my creation is “telling our stories”, “talking about us”.

Telling his story, as a Martinican, is also obvious to Fabrice Théodose: “I am a Caribbean, with all that it represents. There are things and ways of thinking that will strike me. This representation of the world is inscribed in my universe. Here, we’re ashamed of the “gwo pwèl”. I don’t have a heartbreak, I have a “gwo pwèl”, so “man ka séré pou disa” (I hide to say that). It’s us, I can’t pretend. (…) When you write, when you’re in a creative exercise, you’re porous to everything that happens. As soon as I heard someone who had a “gwo pwèl” I would listen to pick up a quote, stories told by friends. There’s a key passage in the play, it’s a phrase a friend told me: “Man sé mò man pa sa mò” (I would like to die, I don’t know how to die)“.

He has a very specific opinion on the Creole language: “Creole is us too, I chose not to translate the passages in the play. I speak Creole to my daughter as I speak French to her. I don’t want Creole to be the language of “man faché” (used when I’m angry). I love French but for me it must be KantetKant, on a relationship of equality, I refuse the dominant-dominated relationship between these two languages because it implies the dominant-dominated relationship on cultures. Creole has never been claimed as much as it is today but, in reality, it is disappearing”.

Gaël Octavia, for her part, has never stopped talking about her native island, even though she no longer lives here: “I still wonder about my legitimacy to speak because I have been living in Paris for about twenty years. There are certainly things I don’t understand. The dismantling of Schoelcher’s statue, it was hard for me to imagine when I lived in Martinique. I don’t realize how people experience these events. Is what they express representative of their generation? Or representative of their group? I’m too far away to know, but I’m always a little annoyed when it takes more energy to break than to build”, she explains.

Meeting the audience

“For my taste, “Cette Guerre que nous n’avons pas faite” was not performed enough in Martinique and Guadeloupe”, says Gaël. And she wonders a lot: “it was a little disappointment, that did not interest people very much. It was read at the Francopholies in Limousin and I was able to exchange views with people from Africa. It was very enriching: a dialogue between decolonized and not decolonized. We have a lot of things to talk about, experiences to share. We would really gain from this, to bring out a concrete character in the speeches on the independence of Martinique. What it can look like when you’re not a major power. What room for manoeuvre do we have? With more or less realistic forecasts, hard data, which would allow us to paint a picture of a possible independence and make our decision. Without going into the scarecrow to think that it would be like Haiti, that it would be awful, but without idealizing either. I have rarely heard concrete and constructive speeches about what independence would really be. We are always in a delirium, whether we are for or against”.

“Ladjablès, femme sauvage”, directed by its author, was a great success in Martinique, during its two performances at the Scène Nationale: “I think it’s because it’s a mythical character in the collective imagination that hasn’t been much discussed. Moreover, the themes of the play are in the spirit of the times: feminism, liberation of women’s speech, powerful women etc. That was also my bias. Many women said to me: “thank you, you allowed me to reveal the devil in me” or “I am a devil, I didn’t know it”, she said.

The play was translated by a reading committee in New York, thanks to the ACT project “Action Caribéenne Théâtrale”. “When “She Devil” was read in the United States, it was very interesting. The text was no longer mine, it was travelling. It’s great to realize that it resonates with other people”, she says.

“Le Monologue du Gwo Pwèl” by Fabrice theodose also met with a large audience, mostly female according to the playwright… “This is the 14th performance. People send me private messages. I didn’t expect to have put so many right words on their feelings. A spectator told me that she felt guilty because she never realized the situation her ex found himself after she left him”.

In this period of claims and questioning of symbols, the words of Gaël, Fabrice and Daniely are as many stones that form statues that look like us. Those who have not had the chance to attend the performances of these plays will be able to discover them through reading. They are now part of Martinique’s theatrical heritage.

“Cette guerre que nous n’avons pas faite” by Gaël Octavia – Éditions Lanzman

“Le Monologue du Gwo Pwèl” by Fabrice Théodose – K.Éditions

“Ladjablès, femme sauvage” by Daniely Francisque – Will soon be published in French

“She Devil” in New Plays from the Caribbean – Publication late 2020