There is a common denominator in all the Caribbean peoples often difficult to understand. We do not speak only about the similarities of the geographical zone that shares our region of tropical climate, bathed by one of the world’s biggest salty seas. Not. There is something intangible that characterizes us, that unites us beyond the visible sociocultural and linguistic differences that are part of this geographical area. It’s our identity.

We notice that this subjective common denominator – in our eternal wish for calling things by their proper name – is called “identity”. Well then, we say that there is on these lands a common cultural identity from a profound and complex miscegenation, that distinguishes us and it is a reality whose unity is improved that, frequently, it is impossible to talk about a region without involving others. Let us say loudly and clearly : to be born and to live in the Caribbean it is much more than belonging to an island.

An Amerindian cultural unity

An Amerindian cultural unity

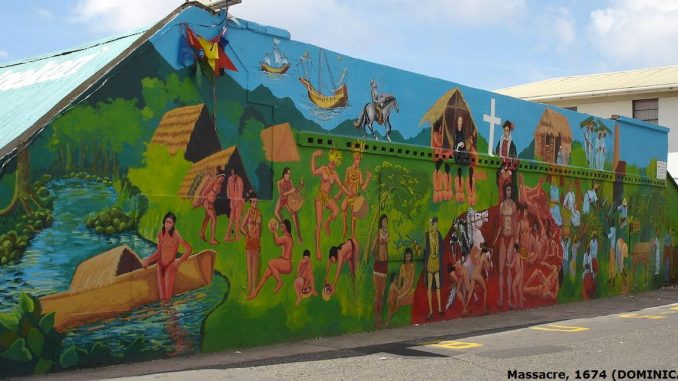

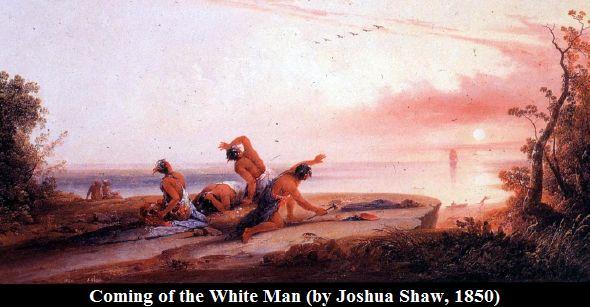

However, to understand this identity diversity that unites the islands which form the West Indies arc and its social and historical processes, we must go back in history. We need to start from the common origin of European conquest and colonization, with the miscegenation caused by forced migration, slave trade and immigration from other continents.

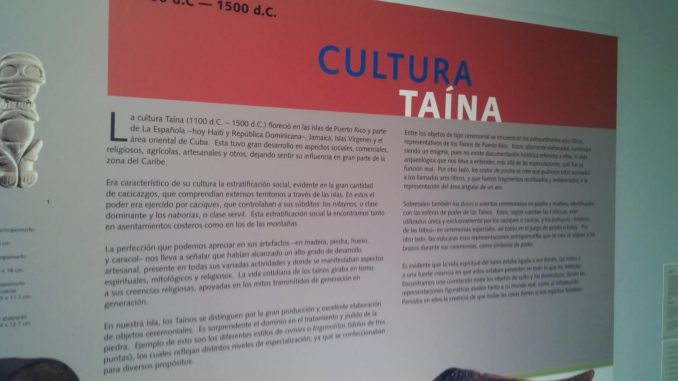

Before the arrival of Europeans, the West Indies arc was populated with groups from the Arawak South American ethno-linguistic trunk who arrived, in large successive waves and so, for centuries, until the eras just before the conquest in the 15th century when these different cultural levels were already interrelated.

According to Cuban historian and researcher Olga Portuondo, this fact “is an opportunity to talk about a cultural unit of Neolithic and agr-pottery period on the Caribbean lands, under the present state of knowledge, it can be confirmed by the traces of its cultural expressions”1.

It follows that, in the forge of the Caribbean identity and with this first great unity of Arawak groups who populated the Greater and Lesser Antilles and the continental coasts of the Caribbean a few centuries before the arrival of Christopher Columbus, it is inevitable to coincide the geographical limits with the ethno-cultural limits.

A clash between Amerindians and Europeans

A clash between Amerindians and Europeans

The word “Caribbean” comes from those Arawak seafarers who settled over all the West Indies. Geographically speaking, the countries bathed by its sea are included in this area : Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Belize, Guatemala and Mexico ; as well as three main areas which strech in a curved shape to the coast of Venezuela : the Bahamas archipelago ; the Greater Antilles with Cuba, Hispaniola (Haiti and Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico and Jamaica ; and the third called the Lesser Antilles, divided in the leeward islands2 and the windward islands3.

As we mentioned before, in the formation of the “Caribbean” there was a first large unity and, although there were cultural variations, remained the same neolithic development and, until a certain point, it was theological because in the religious beliefs and in the pantheon of gods, the tropical nature with its violent meteorological reactions, was always present.

However, with the arrival of the Spanish colonization – under the mandate of the Catholic Monarch and Charles I – his hegemonic position in the Caribbean sea and the frustrated attempts for remotly maintain the ambitions of other empires as Portugal, Holland, France and England, which finally took away pieces of his conquests in the so-called New Continent, the indentity ot the Caribbean man “drank” from many cultures.

An impérialism from the new United States

An impérialism from the new United States

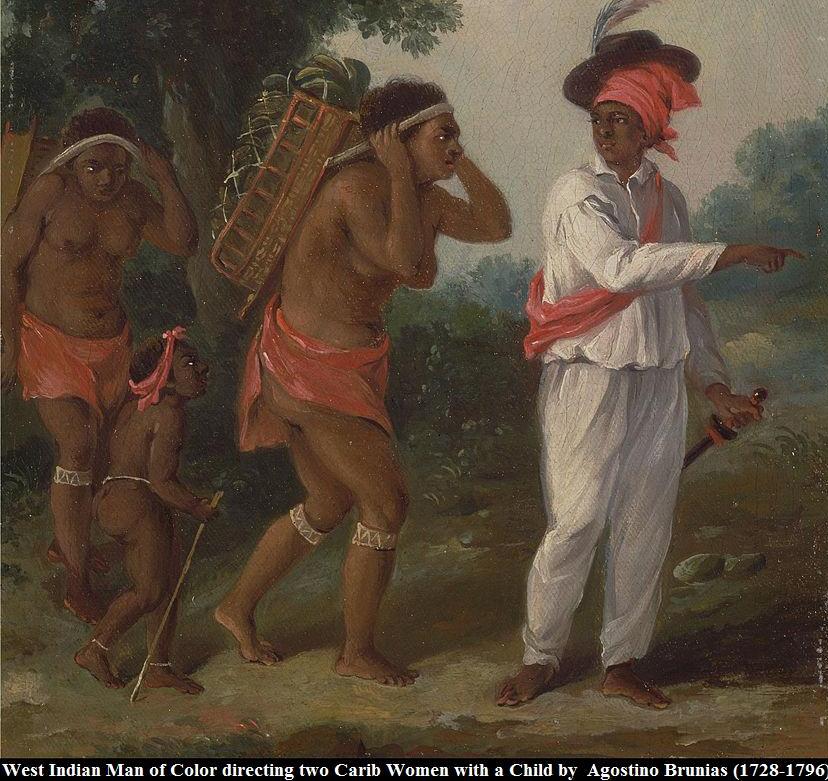

Moreover, from the early beginnings of the colonization, the traffic of black slaves appeared to replace the indigenous workforce whith a population who passed away because of the exploitation to which it was subject, the economic changes and the biological shock because it did not have immunity to face up to the conquerors’ diseases.

Spain lost Caribbean hegemony by the late 1500s and looked at with helplessness how they took its colonies in the West-Indies. After 1824, the Spanish Overseas Empire was restricted to both Greater Antilles – Cuba and Puerto Rico – while Santo Domingo, in the island of Hispaniola, was incorporated into Spain in March, 1861.

On the other hand, when it finished the war against Great Britain, the young North American nation showed signs of its expansionist interests towards the Caribbean. Then, at the end of the 19th century, the region was marked by threats of political instability.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the exercise of imperial authority of the United States, with a lot of economic and military interests, separated the Caribbean islands and coasts. However, despite the respective metropolises set up in the region, which denied the miscegenation, regarded it as a sign of inferiority and recognized only the European white culture, the Caribbean man with his intellectuality began to recognize the undeniable cultural presence of the African, with an almost unilateral opinion.

An African and diverse influence

An African and diverse influence

There is no question about it : the real idiosyncrasy of the Caribbean has in its body the contributions of the slaves, victims of the work in the tropical plantation from the 17th until the 19th century, and also a profound aboriginal trace. “To accept inside the Caribbean nature the natives of these lands is to accept as premises, in the first place, that the extermination of the Arawak was not absolute and, secondly, his cultural heritage ; because we must not forget the Indian mother, a powerful vehicle for cultural transmitting to the half-breed son who has a European or an African father” 4.

Although the diversity of cultures, languages and religions which gather in the Caribbean territories does not allow to speak about the same European, African or indigenous influence which, after, is enriched with the contribution of Chinese, Indians, Arabs, none of these differences prevent the search and the reality of a common Caribbean identity.

More similarities unite us – and not only geographical – than differences. This is the Caribbean, a territory where its peoples enjoy life, where they dance, where they sing, where the sugar cane is cultivated, a good rum is tasted and a good tobacco is enjoyed. This is the Caribbean, the place where this common denominator that we call “identity” stops being a utopia and becomes a latent truth.

1 – Zúñiga Portuondo, Olga. Caribe, raza e identidad. Ensayos críticos de nuestra historia. Editions Unión, Havana, Cuba. 2014, pp.11

2 – Islands distributed between the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Venezuela, located opposite to the coasts of the latter country and on the South American continental platform.

3 – Islands that delimit in the eastern part the basin of the Caribbean Sea, made up of the northern islands of the Lesser Antilles. Some of the principal islands are Grenada, Martinique, St Lucia, Barbados, Guadeloupe, Dominica, Trinidad andTobago.

4 – Zúñiga Portuondo, Olga. Caribe, raza e identidad. Ensayos críticos de nuestra historia. Editions Unión, Havana, Cuba. 2014, pp.95