In recent years, gwoka has got over obstacles but it was not always this way. Indeed, during slavery, the article 16 of the Edict of Louis XIV, King of France, in March 1685, known as the Black Code, prohibited gatherings of slaves who devoted to this music (dance and song) and also imposed sanctions on the slave owners who would authorize them. It’s true, this music that became an instrument of struggle against the colonists, allowed slaves to communicate especially during revolts on the plantations. Today, gwoka did not lose its meaning of the struggle. It is very often used by the strikers who want the employers hear their wage claims.

In recent years, gwoka has got over obstacles but it was not always this way. Indeed, during slavery, the article 16 of the Edict of Louis XIV, King of France, in March 1685, known as the Black Code, prohibited gatherings of slaves who devoted to this music (dance and song) and also imposed sanctions on the slave owners who would authorize them. It’s true, this music that became an instrument of struggle against the colonists, allowed slaves to communicate especially during revolts on the plantations. Today, gwoka did not lose its meaning of the struggle. It is very often used by the strikers who want the employers hear their wage claims.

A music of joy and sorrow

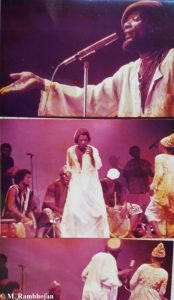

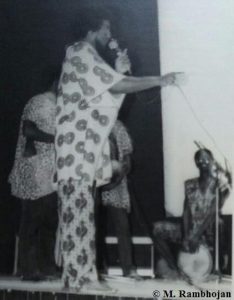

However, this musical weapon was also used to convey joyful and sad emotions. This music that the rapporteurs and missionaries to the 17th from the 19th century called “calenda” hosted festivities after religious ceremonies such as baptism ; the “drum beat” also thrilled the weddings. Gwoka was present during the patron festivities in the popular districts of the city and in the country.

On that subject, during the awareness period, since the 1990s, the towns began to appeal to gwoka groups to organize “léwòz” or concerts during the patron festivities. Today, it is not unusual to notice that each district of a commune claims its “léwòz”.

Gwoka accompanied the death of a loved one. Today, during a wake, some families invite musicians, singers and dancers (when they do not come spontaneously) to “sound” the drum-ka until dawn to honour the passage of a close on the other side.

A democratized gwoka

A democratized gwoka

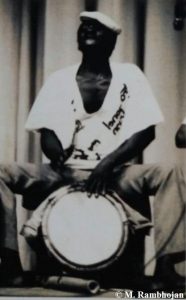

In spite of everything, the advocates of this music-song-dance that belongs to the Guadeloupean cultural heritage know that gwoka has not finished its Way of the Cross towards full acceptance. Several phases have already contributed to make positive gwoka : creation of groups wich produce or not CDs ; publication of methods facilitating the practice of gwoka music and gwoka dance ; creation of music and dance schools ; setting up of craftsmen who make the ka-instrument for the “tanbouyé” (ka-drum players) and for the people who put this drum in their living room as a work of art ; creation of the “Sainte-Anne gwoka Festival” which attracts, every year, thousands of people ; increase of carnival groups using the traditional drum, known in Creole as “gwoup a po” (“skin group”, because of the goat skin covering the drum), for 25 years.

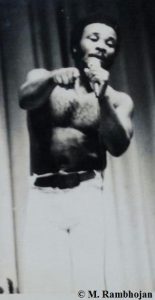

“Vélo” as a God

the reputation of Gwoka as a “biten a Vye Nèg” in Creole (something reserved for bad Negroes, in English) is difficult to erase even if this music now penetrates in many homes.

the reputation of Gwoka as a “biten a Vye Nèg” in Creole (something reserved for bad Negroes, in English) is difficult to erase even if this music now penetrates in many homes.

50 years ago, the “tanbouyé” were chased away the streets of cities by the police if they dared to play this drum. Among them, there was Marcel Lollia, nicknamed “Vélo”. The master tanbouyé who slept in the street with alcohol as a good friend, died June 5, 1984. Nearly 6000 people attended his funeral… an unprecedented event in Guadeloupe, at that time. Today, “Vélo” became a guide, a father and even a God for many gwoka players who claim to take their inspiration from him. Moreover, zouk music singers put the drum-ka as a “guest of honor” in their compositions…

A stigmatized gwoka

Moreover, eleven years ago, after a passer-by being assaulted near musicians who were playing gwoka in the street, the municipality of Pointe-à-Pitre decided purely and simply to ban this music in the main roads of the city. Many people did not understand the meaning of this bylaw of June 22, 1995.

Moreover, eleven years ago, after a passer-by being assaulted near musicians who were playing gwoka in the street, the municipality of Pointe-à-Pitre decided purely and simply to ban this music in the main roads of the city. Many people did not understand the meaning of this bylaw of June 22, 1995.

This decision caused an outcry from gwoka fans who thought that delinquency was responsible for this attack but not their music… Then, the sound of the drum-ka was heard throughout the city until this bylaw was withdrawn. It must be said that, since the 1980s, a movement encourage the Guadeloupeans to appropriate their cultural heritage.

At the moment, the “tanbouyé” play, dance and sing gwoka in the streets of Basse-Terre and Pointe-à-Pitre, including the pedestrian street where was erected the statue of “Vélo” to the great delight of the Guadeloupeans and tourists.

Gwoka music, born in the sugar cane fields in Guadeloupe, considers itself to be the cousin of blues music, born in the cotton fields in the United States.